August 14: 1921, 1981, and 1991

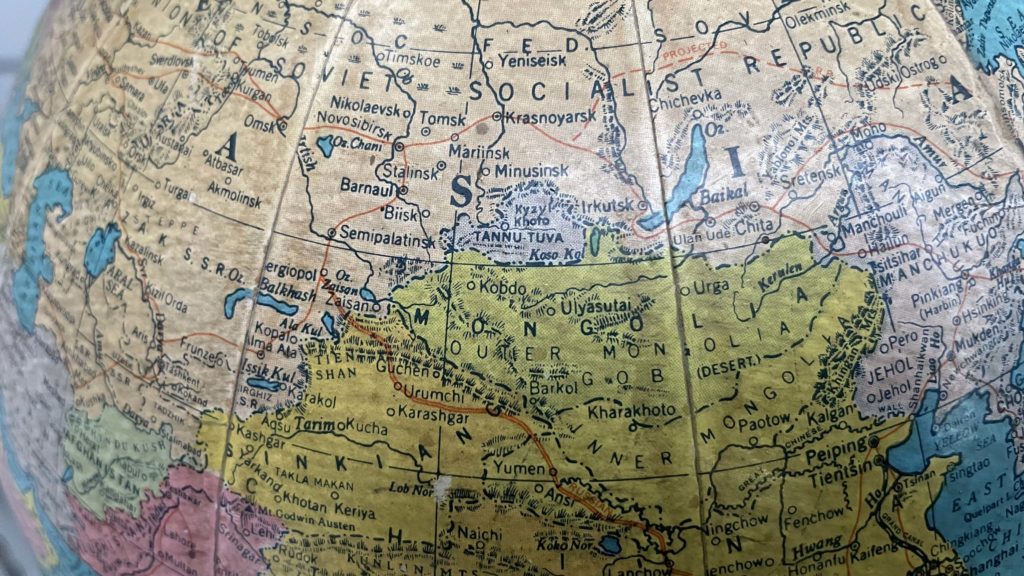

Ever since I learned of the “lost land of Tannu Tuva,” I was aware that August 14, 1921 was significant: my understanding was that Tuva declared its independence from Mongolia on that date, and for 23 years “Tannu Tuva” appeared on maps as a separate country, often colored pink or purple.

For many of those years Tuva (or “Touva”) issued dozens of fantastical stamps, many of them triangular or rhomboid in shape, captivating collectors around the world—among them a young Richard Feynman. If you need more background, you can read my 1991 book Tuva or Bust!

August 14 was so significant that I (inadvertently) founded Friends of Tuva on August 14, 1981 by sending out greetings to my friends and acquaintances commemorating the date and its significance, and followed up with several newsletters that have since been preserved on the website FoTuva.org, thanks to the most honorable and appreciated Kerry Yackoboski.

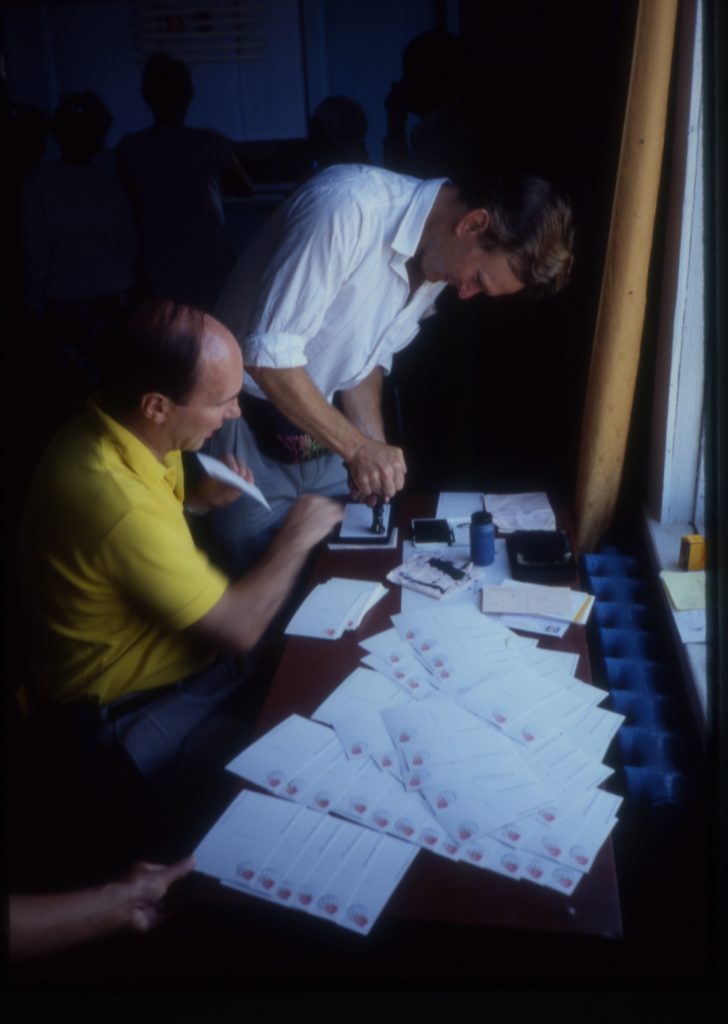

Ten years later I found myself in Tuva, in the village where independence was declared—Sug Bazhy (Kochetovo today)—along with my philatelist brother, Alan, and the illustrious Simon Winchester, who had written a wonderful article about Feynman and Tuva for the in-flight magazine of the Belgian national airline Sabena. Winchester surprised us in Kyzyl with a Victorian-era, Henry-Morton-Stanley-like appearance out of the blue with the words, “Dr. Leighton, I presume?”

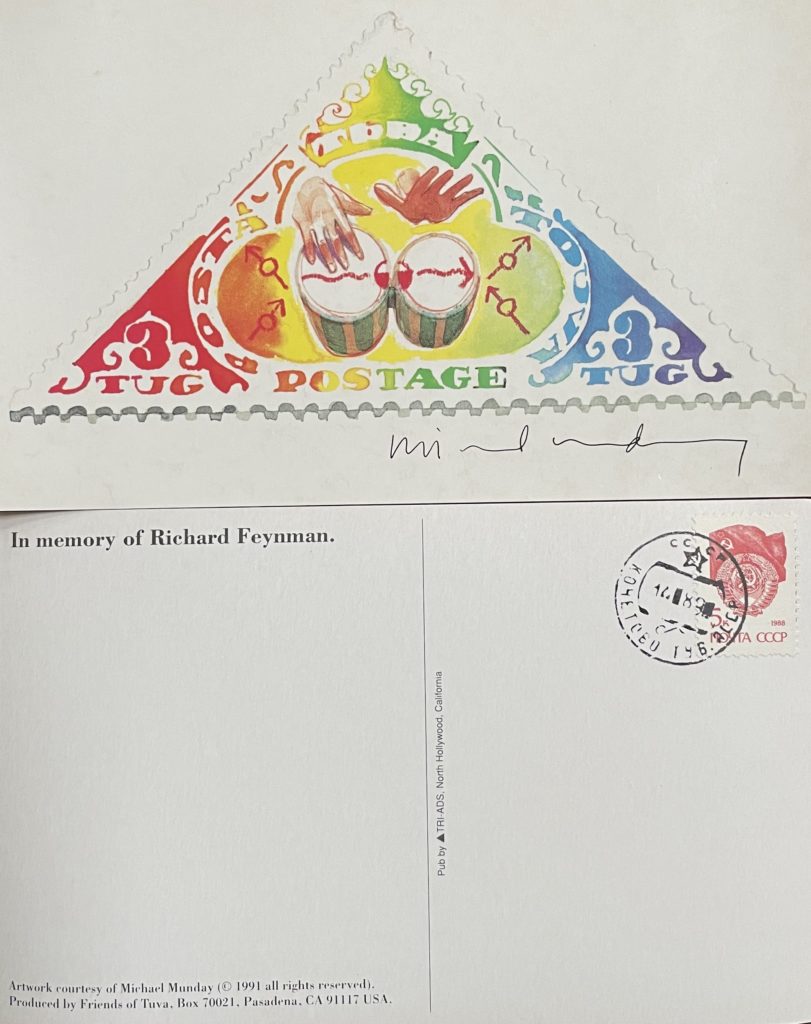

In Kochetovo we postmarked dozens of postcards in honor of Richard Feynman to commemorate Tuva’s 70th anniversary.

The fantasy postage stamp on the front of the postcard was created by Michael Munday for the Winchester Sabena article.

Apart from our own gesture in Kochetovo, there seemed to little interest by the government at that time in commemorating Tuva’s founding; the only celebrations we saw were the annual summer Naadym festival of wrestling, archery, and horse racing held every mid-August in Tuva’s capital, Kyzyl.

2021 on the horizon

As the centenary of the founding of the Tannu Tuva Republic approached, I did not want to invite myself by asking the government of the Russian Federation for permission to be in Kochetovo on August 14, 2021 to celebrate the founding of the independent Tuva Republic—for all I knew, there would be no centenary celebration, just like there had not been any festivities on August 14, 1991. Think of it: did the US government commemorate the centenary of the briefly-independent republics of Texas (1836) or California (1848)? I don’t think so.

Therefore, I was surprised and delighted when I received birthday greetings near the close of 2019 from Zoya Kyrgys, the preëminent researcher of Tuvan throat-singing and Tuvan culture in Kyzyl, which included this: “I hope to invite you to Tuva with the help of the Tuvan government in 2021 (100th anniversary of the Tuva Arat Republic).” The “Tuva Herders’ Republic” (abbreviated TAR for Tyva Arat Respublik) is another name; its official name upon its founding was ВҮGҮDE NAYYRALDYG TAҢDY-TYVA ULUS, or Republic of Tannu-Tuva People. In Russian, it’s often abbreviated TNR for Tuvinskaya Narodnaya Respublika (ТНР Тувинская Народная Республика) for Tuvan People’s Republic. So now you’re up on your Tuva Repubic nomenclature!

I was elated, and began dreaming again: there would be centenary celebrations after all, and I was invited!

Then came COVID-19.

Visa issues

Throughout 2020, governments around the world shut their borders to travel, and the Russian agency for reviewing invitations to foreigners shut down indefinitely. I therefore put aside my dream of being at “the place where it happened” on August 14, 2021.

But COVID-19 had another, indirect effect on my prospects for reaching Tuva in 2021: it provided time to translate my book Tuva or Bust! into Russian. The translator was none other than Dina Oyun, who is now a senator in the Federation Council, the upper house of parliament of the Russian Federation. Ms Oyun appears briefly in the Oscar-nominated film Genghis Blues as the emcee of the concert Paul Pena performed in for the throat-singing festival in Kyzyl, Tuva (organized by none other than Zoya Kyrgys) in 1995. So now you’re up on your Genghis Blues news!

So now there was an additional reason to invite me: to launch the Russian translation of Tuva or Bust! With Russia closed to nearly all outsiders, if it took an “act of Congress” to allow one to enter the Russian Federation, it was good to have a senator in one’s corner. (As it turned out, an “act of Congress” was not needed, but a letter of support from a Deputy Prime Minister of the Russian Government to Senator Oyun on my behalf was pivotal several months later.)

In January 2021, the term of the Russia-friendly president of the USA was over, and relations between the two countries sank to a level not seen since the Cold War thirty years before. I figured that Washington, DC was not going to be a good place to get a visa, for practical as well as political reasons. Instead, we would “embassy shop” to find a European country that 1) had good relations with Russia, and 2) would let in citizens of the USA despite the Covid situation.

That narrowed down the list considerably. Phoebe and I decided to visit several countries along the Adriatic coast across from Italy during the early summer. If things didn’t work out to get to Tuva, we’d at least have a nice vacation. As for Russian embassies, I emailed four: in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Montenegro. Slovenia and Bosnia did not respond; Croatia gave a bureaucratic answer (“If you receive an invitation approved by the Federal Migration Service, then contact the following office…”), but Montenegro (the smallest of the four) was emphatically a yes: with an official invitation in hand, we could get a visa in less than two days.

Everything seemed on track until we reached Montenegro: our official invitation had not been issued yet, so we reluctantly turned around and headed back to Slovenia, where we had picked up our rental car.

Just as we were about to embark on Plan B (Italy), our invitation arrived. It was August 6. The centenary celebrations would begin in exactly one week. We found a flight to Montenegro on Air Serbia, and presented our passports on Monday, August 9. If the embassy delivered as promised, our visas would be in hand by Wednesday, August 11 at the latest.

My application was promptly approved; Phoebe’s was not: there were not two consecutive blank pages in her passport—one for the full-page Russian visa; the following page for entry and exit stamps. We were instructed to get extra pages put into Phoebe’s passport, a service provided (up until 2016, we soon found out) by the local US embassy. We returned the next day (Tuesday), explaining that no additional pages could be added—and on top of Phoebe’s passport I put the letters of support from the Deputy Prime Minister of Russia and Senator Oyun from Tuva.

The visa officer glanced at the letters and said, sternly, “Two pages!” —long pause, for dramatic effect—“…but for you, I make ex-cep-tion,” spitting out that last, crucial word.

I bowed briefly in thanks—and asked how long it might take to process our visas: after all, our visas could be approved, but then delayed long enough in processing that we would miss the celebrations. Two more days, maybe?

“Come back in one hour!”

Now, at last, we could try to find flights from Montenegro to Moscow that would get us to Kyzyl in time for the centenary celebrations. Possible itineraries varied widely in geography, time, and price, but we finally settled on an 18-hour journey via Warsaw, beginning early on Thursday, August 12.

Thankfully, all the flights (WizzAir, Aeroflot, and IrAero) were on time—two out of the three were airlines we had never heard of, but they were perfectly fine. The most harrowing part of the journey was on the ground in Moscow, transferring from the international Sheremetyevo airport to the domestic Domodedovo airport—which was kindly arranged for us by the tech-savvy, entrepreneurial Ali Kuzhuget, who hails from the extremely rural western part of Tuva, and who now works in the extremely urban, Dubai-esque district called Moscow City. We had just enough time to meet and take a picture among the high-rises.

Touchdown!

Phoebe and I arrived, bleary-eyed but excited, in Kyzyl on the morning of Friday, August 13; that afternoon we were witnessing a solemn ceremony, replete with goose-stepping Russian soldiers, paying tribute to the founding of the Tuva Republic. Tuvan Senator Oyun was part of that ceremony.

An hour later, we were in a new wing of the Tuva Republic Museum, which houses many of the dramatic “stone men” carved over the centuries in Tuva. I immediately recognized one of them: it was on the cover of Otto Maenchen-Helfen’s Reise Ins Asiatische Tuwa, an eye-witness account of Tuva in 1929, which had served as our lodestar back in the 1980s when Feynman, Glen Cowan, and I were trying to reach “the lost land”: how much of the Tuva depicted in that book, and on the stamps from that same era, still survived, we wanted to know. My philatelist brother, Alan, and I got to find out for ourselves in 1991 (just as the Soviet Union was dissolving)—and now, Phoebe and I could experience Tuva thirty years after that.

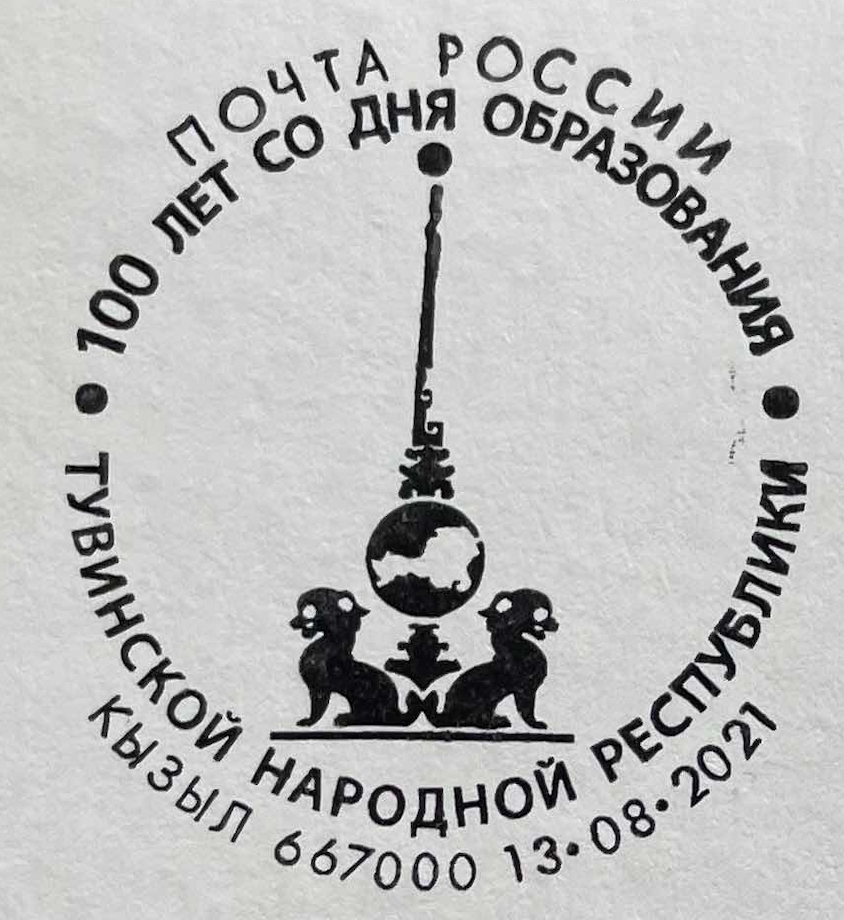

The new wing of the Tuva Republic Museum was the site of a ceremony dedicating a commemorative centenary postmark. Attending the ceremony was Tuva’s head of government, Vadislav Khovalyg, seen here with the Museum’s director, Kadyr-ool Bicheldei.

Senator Oyun was there, along with Kyzyl’s postmaster. The next thing I knew, I was invited to stamp the commemorative centenary postmark along with them. Dated August 13, 2021, the postmark says (in Russian), “100 years from the day of formation of the Tuvan People’s Republic”. Bravo to Pochta Rossii, the Russian postal service!

Wait: August 13? Not August 14?

I was told that the gathering in Sug Bazhy (present-day Kochetovo), where the Tuva Republic was proclaimed, began on August 13—and concluded on August 15, 1921 with the adoption of a constitution. OK, so the average was August 14, then?

What about Kochetovo?

Celebrations in Kochetovo had taken place earlier that day. Phoebe and I had arrived too late to attend them.

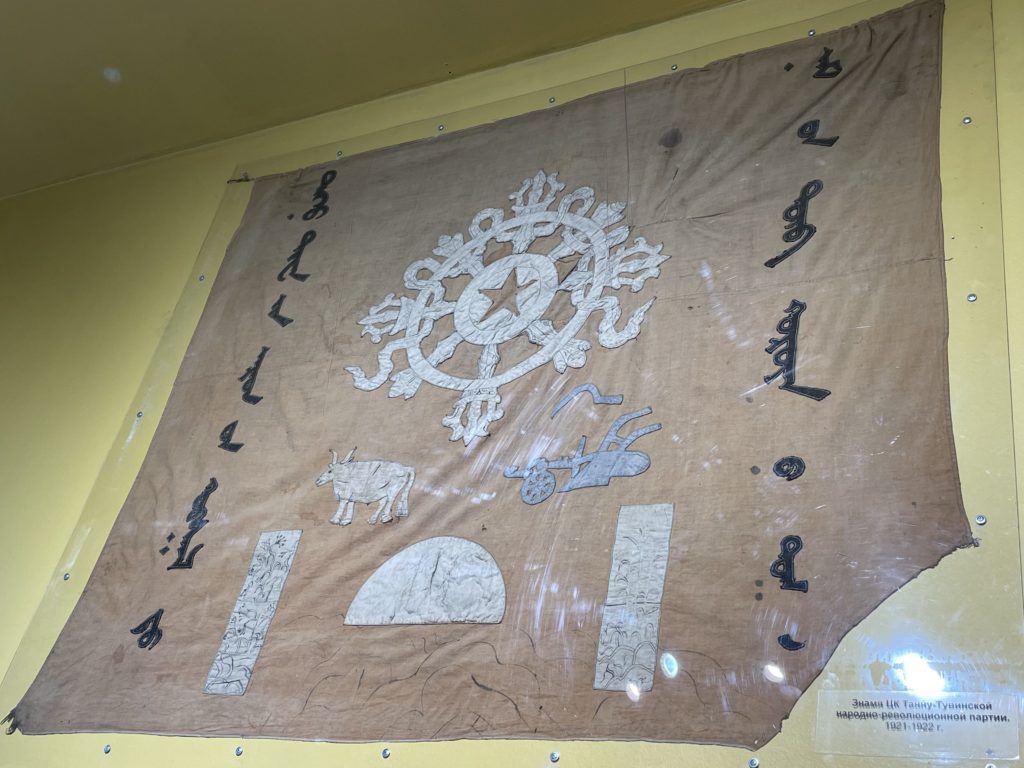

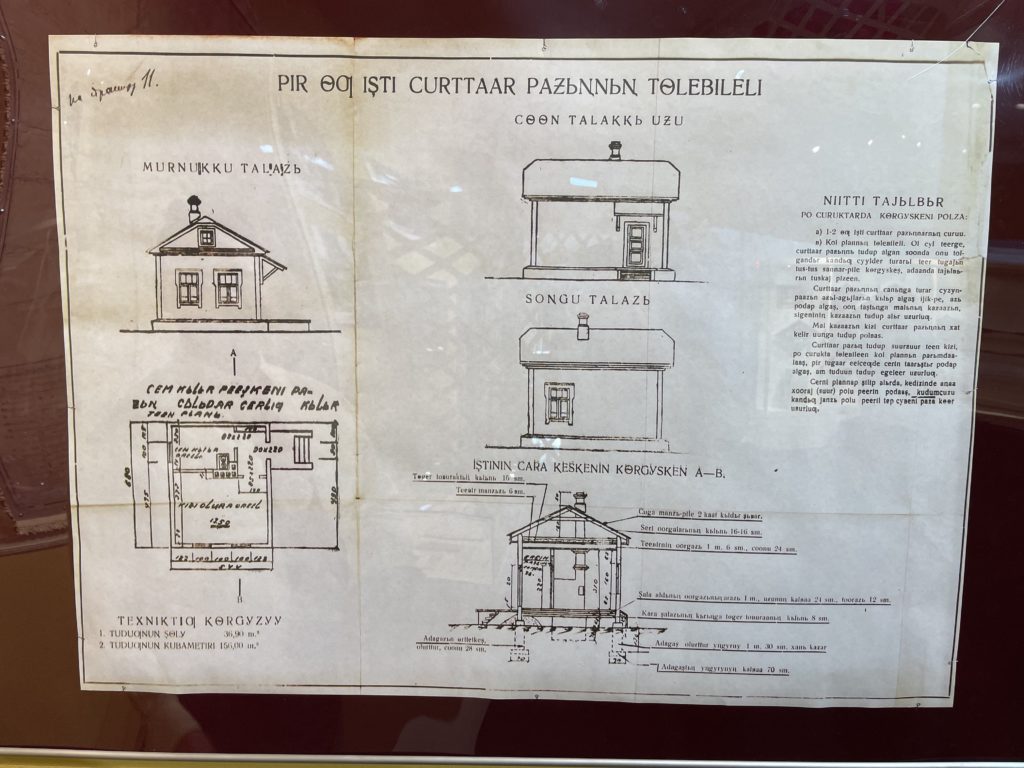

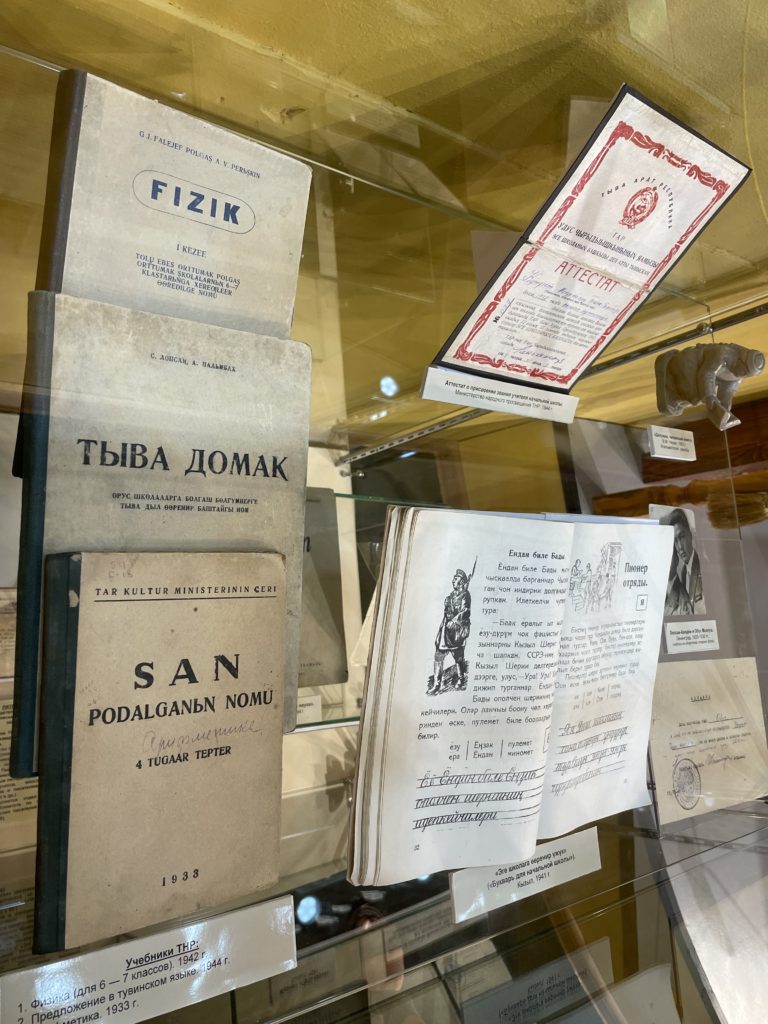

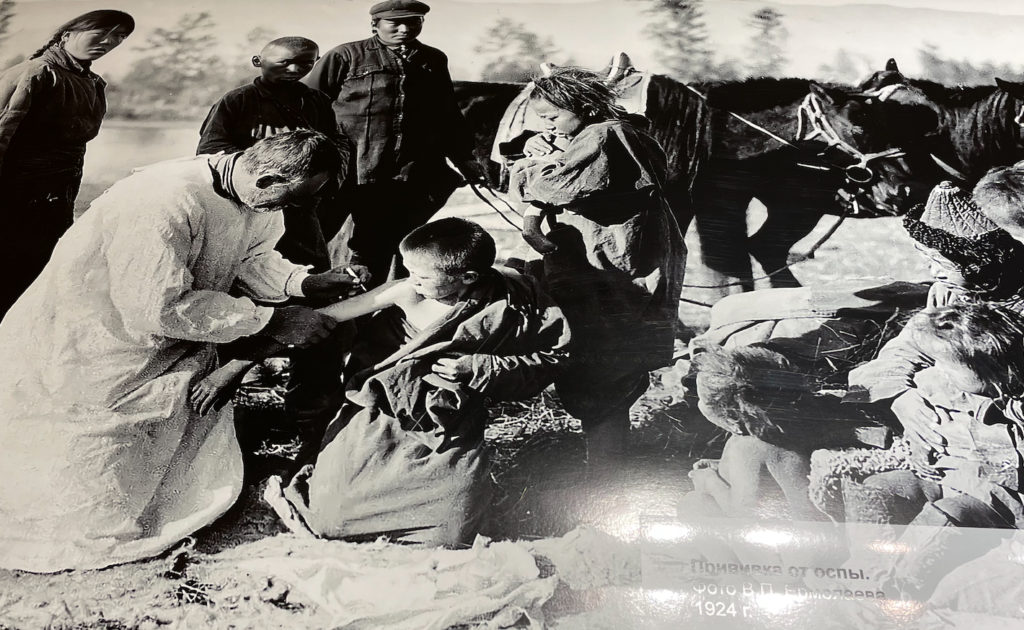

Our disappointment was quickly overcome when Khülerben Kadyr-ool, the Assistant Director of the Tuva Repubic Museum, provided us a personal tour of a special exhibition on the Tuva Republic. (Due to Covid, the exhibition was closed to the public; it was set to reopen as soon as the Covid numbers decreased sufficiently.) There we saw the original Tuva Repubic flag, blueprints for a house that people were encouraged to build by the government (as yurts can be really cold and drafty in winter, which lasts six months in Tuva), a book on physics written in the Tuvan language for 6th and 7th graders (oh, how Feynman would have loved to see what was inside!), and—especially appropriate for the present day—a photo of a child being vaccinated (against smallpox, presumably).

August 14 or Bust!

Since I was so attached to August 14, I was determined to find a way to get to Kochetovo the following day, Saturday. Thanks to Enrique Ugalde (a throat-singing performance artist who lives part-time in Tuva), we were able to get in touch with Tuva’s former Minister of Culture, Aldar Tamdyn (a throat-singer himself), who made some phone calls and accompanied us to Kochetovo.

The town was eerily quiet—no signs of any celebrations except for the fresh paint and the huge banners that had greeted the VIPs the day before. The photo shows my wife, Phoebe, with the daughter of our (now departed) Tuvan correspondent Ondar Daryma, who had the courage to answer our letters written to his institute more than forty years ago.

The local museum guide opened the museum and gave us a personal tour of Tuva’s “room where it happened,” a log cabin with a special underground escape tunnel (look carefully below the red tablecloth), in case the signers of Tuva’s declaration of independence and constitution were threatened. (As it turned out, the choice of an out-of-the-way place to proclaim a new republic was a wise one; the Mongolian rulers had no idea of what went down until well afterwards.)

By the way, the constitution included a clause for freedom of religion, as well as one for government responsibility for health care, among other interesting items. Here is a Google translation of the “declared constitution”, which was written in Russian, and was based on a draft written in Mongolian.

A special postmark

There still remained the matter of the post office: having postmarked a stack of cards in the same spot exactly thirty years before, I was set on doing the same in 2021. Problem: the post office was closed—not because it was Saturday, but because the postmaster, the one-and-only person who worked there, went on maternity leave—starting on (drumroll, please) August 14!

Somehow Tamdyn got her cell number, and before long the called-back-from-her-first-day-of-maternity-leave postmaster graciously opened the post office, adjusted the postmark to August 14, and started stamping away. She even lent me the stamp to “cancel” a few Feynman postcards of my own. After a few minutes the stamping was finished, and the post office doors closed again, not to reopen for several months. To my knowledge, the only items in the world postmarked August 14, 2021 in Kochetovo, Tuva are those specially canceled Feynman postcards.

Here’s a video of the post office adventure.

So now the first objective of our journey to Tuva in 2021 had been accomplished: to celebrate the centenary of the Tuva Republic. In three days would come the second part: the release of the Russian translation of Tuva or Bust!

Feynman Rock

The break allowed us to make an excursion out to Feynman Rock, 90 minutes by car (or, better, jeep) north of Kyzyl. It was carved by stone masters George Gonzalez from California and Orlan Sat from Tuva in 2018 to commemorate the centenary of Richard Feynman’s birth on May 11, 1918. The weather in May in Tuva is typically crisp and clear, with spring finally breaking out. Most importantly (at least as far as visiting Feynman Rock is concerned), the mosquitos haven’t appeared yet in May.

August is another story: there were clouds of the little blood suckers “welcoming” us, and it was hard to get a photo without getting bitten. But our annoyance at the mosquitos was forgotten when we interacted with Enrique’s son, Quito; he is a real joy to be around, and has the distinction of being the only Tuvan with Mexican heritage, as far as I know.

After a much-needed day of rest on August 16, our next big day began early, with a ceremony at a dramatic overlook of the Yenisei River, an hour downstream from Kyzyl. A sacred fire was built, a shaman performed a blessing, and several dozen of the world’s greatest practitioners of the art of khöömei chanted in an eerie, wonderful concentration of sonic and cultural energy, which permeated all who attended.

Check out this video of Khöömei Day!

It was a dramatic and fitting start to International Khöömei Day (August 17), celebrating the art of Tuvan throatsinging, which now has fans around the world.

Then the action moved to the Tuvan Cultural Center in Kyzyl, where the Russian translation of Tuva or Bust! was officially released, along with the awards for the best performance of kargyraa (this year’s category of throatsinging). In the group photo, you can easily spot the doyenne of Tuvan khöömei research, Zoya Kyrgys, who started the ball rolling for my invitation to visit Tuva in 2021: she is the only one wearing a mask.

Into the countryside

With the two main goals of my visit to Tuva now accomplished, Phoebe and I had a week or so to travel into the countryside. The southern border area with Mongolia (camel country) was unfortunately closed to us, but we went up to Tozhu kozhuun (kozhuun = district) in the northeast in search of reindeer herders, and then out west to Bai Taiga kozhuun in search of yak herders—with those marvelous Tuvan stamps as our inspiration.

In years past, it was rare to reach reindeer herders except by helicopter, as they were always in such remote parts of Tuva. But after a few hours on a gravel road shared with mining trucks, we discovered a family of reindeer herders who had set up camp a few kilometers off the road in the hope of attracting some tourists. We happily obliged, and even got to ride one of the larger animals.

A few days later, on the way out west in search of yaks, our guide showed us rock drawings and stone statues from centuries past, from Scythian and Turkic times.

We traveled up the Khemchik River from Teeli, and met some herders moving from their summer camp to their fall camp—but no sign of yaks. One of the horsemen had a friendly race with us for about 10 kilometers.

Here’s a video of the friendly horse-vs-car race.

We decided to stop looking for exotic animals and instead sought out the source of the Alash River, where it emerges from Kara Khöl (Black Lake, named for its deep water). (Many a Tuvan song extol this river, and the Tuvan singing group Alash has taken its name.) On the way we passed a rebuilt lamasery (Stalin had burned them all in the 1930s) and overnighted at the sacred spring Arzhan Bel. I thought I recognized the place, and the locals told me, “Yes, we remember you from 1991! We still have your picture that you sent us back then!” Apparently Americans don’t make it out that way very often.

Along the Alash River we passed several burial mounds and stone monuments from centuries ago—there are so many in Tuva that archaeologists have trouble deciding which to investigate further.

It was evening when we arrived at Kara Khöl, and we were in for a treat that night: a group of trainees were going to be led by an elder shaman in prayer! After a feast of mutton, the shamans built a fire and brought out their drums. What a moving, spiritual experience—and what luck (or was it magic?) that those shamans chose the same night as we did to visit Kara Khöl.

Here’s a taste of the ceremony.

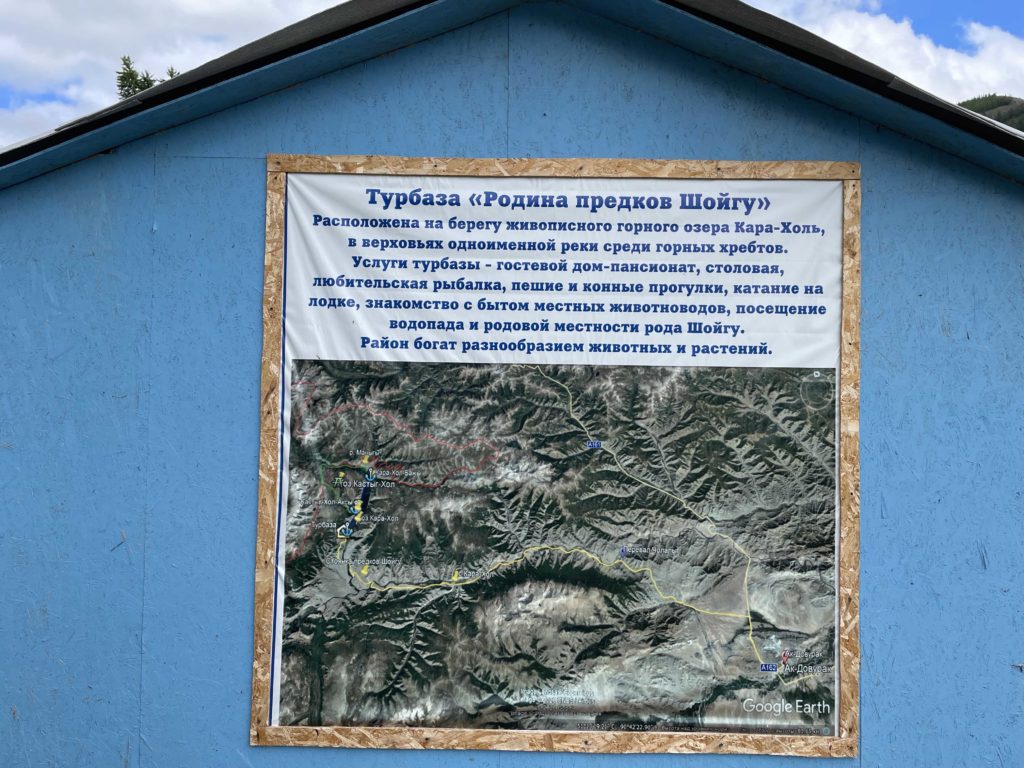

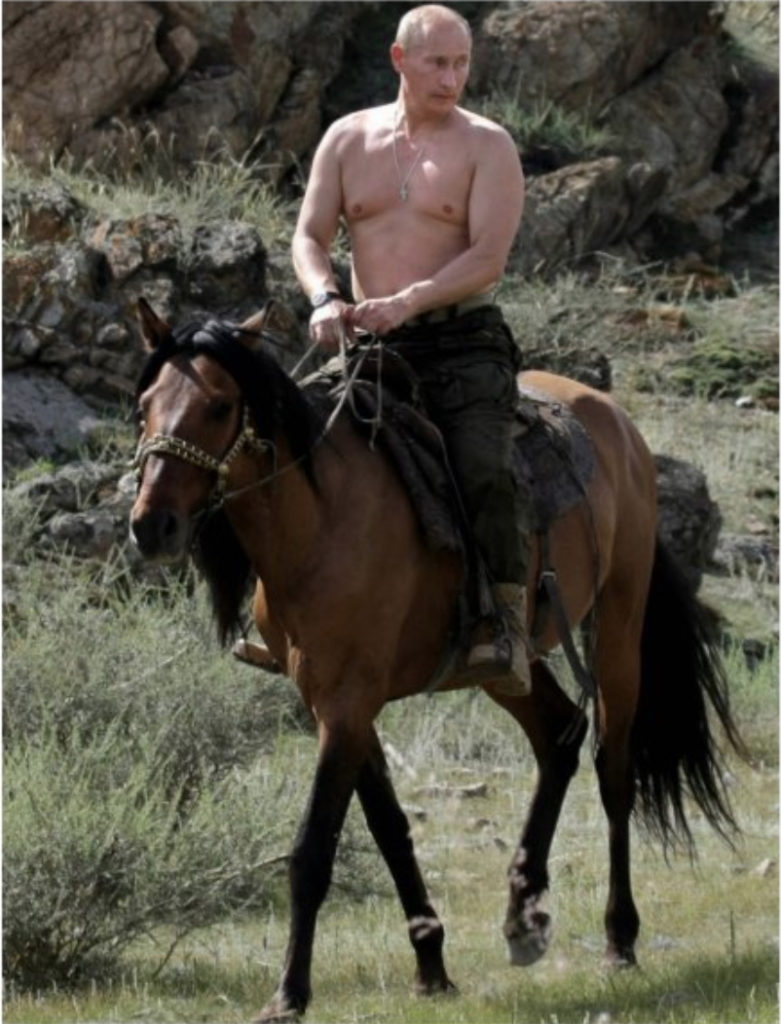

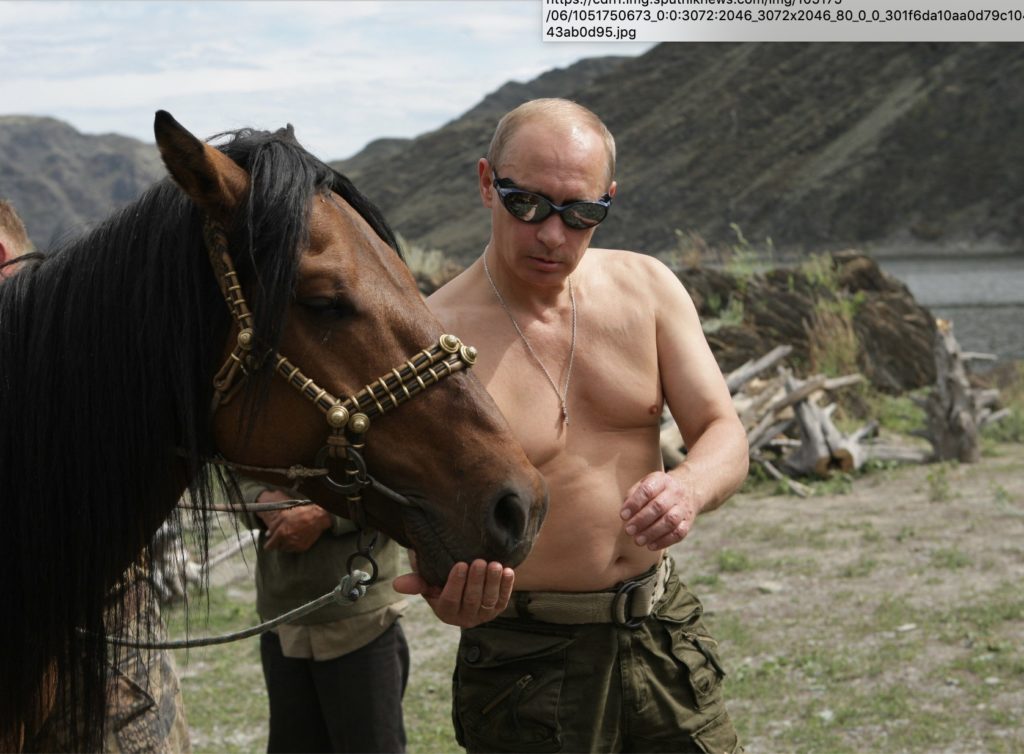

The next day we hiked along the lake with our very capable guide Artsalam (“the lion”) and the extremely talented translator Sonamaa, and saw where the Alash River begins. We learned that this part of Tuva is where the Shoigu clan has several camps that it uses throughout the year. Yes, “Shoigu” as in Sergei Shoigu, the Defense Minister of the Russian Federation, who is a hero in Tuva. He introduced Vladimir Putin to Tuva about a decade ago; it was in Tuva that the (in)famous photos of Putin on a horse were taken.

The next night we stayed in the home of a dairy farmer couple—the one-room house plan seemed to be the one we saw at the Tuva Republic exhibition, with the stove as the center. They served us fresh cottage cheese and tea, and took the visit by four people in stride, with grace.

As we drove back down the Alash River the next day, we encountered what we were no longer looking for: yaks! And then, several hours later, the other animal we were no longer looking for: camels! Our reindeer-yak-camel trilogy from Tuva’s postage-stamps was now complete.

The evening before out departure from Tuva, Zoya Kyrgys had one more surprise, to top off her original invitation: a citation and medal presented by the Tuvan Ministry of Culture recognizing my promotion of Tuvan culture over the past three decades. Nice!

Now that I’m back in California, with fond memories of this summer’s Tuva adventure still warming my heart, I am turning to the next chapter of the Tuva adventure—I’ll have to keep it confidential for now, as I don’t want to jinx anything!

I wish everyone a great finish to this centenary year of the Tuva Republic, and when I find out more about the big festival planned for next summer to celebrate the 60th year of the people’s throat-singer, Kongar-ol Ondar, I’ll post the news on my website.

In the meantime, you can read a beautiful tribute to Kongar-ol.

And you can view (and listen to!) a children’s book (for all ages) I wrote, The Legend of Ondar the Groovin’ Tuvan—enjoy!